Michigan Forest Life - October 5, 2025

- Oct 12, 2025

- 4 min read

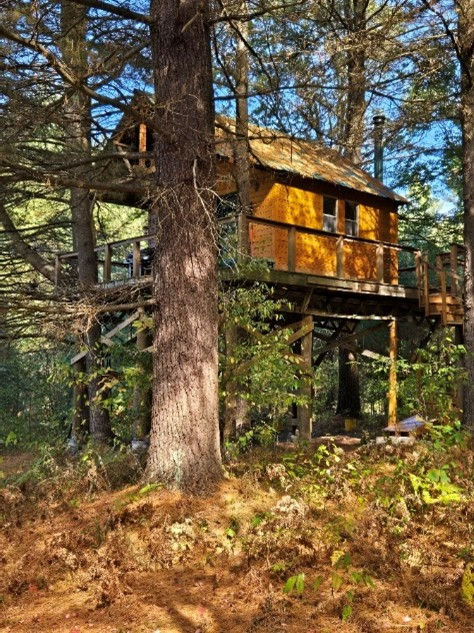

Welcome back to the Treehouse at Winterfield Pines Nature Sanctuary (Photo 1).

When I designed the treehouse in 2005 and we began building it in 2006, I thought in terms of a structure with a twenty-year lifespan. I was approaching fifty years old then and could not imagine using a place like this in the forest beyond seventy years old. I would build it, use it for twenty years, and then remove it from the forest.

I certainly did not expect to spend more than 150 days in the Treehouse each year for more than ten years running. It was a shelter intended for casual use; a way to make using the property easier; a year-round upgrade to a tent.

We built a platform first, supported by three trees and three columns (Photo 2). Nick, our oldest son, helped during the general construction. There have been many times when I was glad I did not wait until I was older to build the Treehouse.

It was designed, and materials selected, for the twenty-year-plan. The structure was built on the platform, and, while it used basic home construction techniques of the time, it also took weight into consideration in a way that would not have been necessary for a structure sitting on the ground (Photo 3). We began to use it while it was being built.

The treehouse is now nineteen years old and in remarkably good condition. I am not nearly done with it. The Treehouse has weathered nineteen years of Michigan's storms - rain, wind, hail, tornados, snow, and ice. I have made three structural repairs to the support platform after major weather incidents.

When the Treehouse was eighteen years old in 2024, I decided to add columns on its east side and disconnect the Treehouse from the trees. I called it "setting the trees free." (Not 100% disconnected, since I installed two new large braces that anchor the structure to the largest tree to reduce side movement)

This year I plan to install three columns under the platform's cantilever on the west side of the Treehouse and remove some of the deflection that has developed in the cantilever over the years. If you look closely you will see three footings installed at ground level, one below

each truss end (Photo 4). I am always charmed by digging in the forest with a shovel to below the frost line, by mixing bags of concrete in a wheelbarrow with hand-pumped water (with the original three columns it was water out of the stream), and putting hand-mixed concrete into the form one shovel at a time. It is slow, taxing work, but the results are good and it is gratifying.

I am happy to announce that because of adequate knowledge, and more experience than needed to meet the requirements, I have finally graduated from an eighty pound bag of concrete to a sixty pound bag. I am happy to have made the graduation and am now motivated to continue my advancement to the forty pound bag when I qualify for such prestige.

As for the new columns - that will be some work. Stay tuned.

Permit me to include another PREVIEW SNIPPET from FOREST LEGEND: THE TALE OF OL' SPLIT TOE (Photo 5).

I wish you motivation to do things that make your life interesting - and the grace to accept a reverse graduation from time to time.

Until next time,

Dan

Snippet 2 of 27

Excerpt from Chapter 1

AD 1409 - Split Toe was not really his name—at least not yet, in 1409. For now, the few humans who had seen him, with the massive antlers adorning his head, simply called him Waawaashkeshi: deer.

European settlers of another age, perhaps around 1900, called him Ol’ Split Toe. Truth be told, these humans did not know enough about Split Toe to understand that he was only one deer. For them, he was a lineage of deer, each with a set of antlers larger than any other. Each one, they called Ol’ Split Toe.

As the remarkable lineage continued, an Ol’ Split Toe appeared in the hunting dreams of the European settlers’ offspring. He was their legendary King of the Forest, who had survived the dangers of the wilds to become the largest and heaviest buck in the woods. Enormous antlers. A huge body. Each deer extraordinarily smart. Almost impossible to take. He slipped past them year after year, outfoxing all their hunting strategies. They knew when Ol’ Split Toe had passed in the night because he left a mark of two front toes split wide apart, followed by two rear points so far from the toes that a human hand could not cover the print.

A lineage of large-antlered deer certainly existed. But these fellows did not know and would never believe the real Split Toe was truly just one deer, a real deer—the Split Toe. Those who saw him were unaware of Split Toe’s movement from one age to another through a natural time portal, the river crossing, which only opened under the shadow of an eclipse. Split Toe’s highly developed instincts always drew him back to the crossing, with the spirits of nature guiding him on a journey toward understanding.

If humans had known he was truly just one deer, they might have thought he was immortal, protected from death. It would have seemed so, for there were many times when Split Toe was lucky to still be alive.

But here, standing on an already-ancient trail at the edge of the tag alder thicket in 1409, he was Waawaashkeshi. And he was in mortal danger.

Copyright @ 2025 by Daniel S. Ellens

Presale Release date: November 25, 2025

Publication Date: March 31, 2026

Praise for FOREST LEGEND:

“A powerful, lyrical meditation on wilderness, myth, and memory. Ellens has created a tale that feels ancient and urgent at the same time.”

– William Gibson, author of Neuromancer and New York Times bestseller Agency.

Comments